Blog

Program Areas

-

Blog

CDD Urges the House to Promptly Markup HR 7890 - the Children and Teens' Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA 2.0), HR 7890

COPPA 2.0 provides a comprehensive approach to safeguarding children’s and teen’s privacy via data minimization and a prohibition on targeted advertising – it’s not “just” about “notice and consent”

COPPA 2.0 provides a comprehensive approach to safeguarding children’s and teen’s privacy via data minimization and a prohibition on targeted advertising – it’s not “just” about “notice and consent”We commend Rep. Walberg (R-Mich.) and Rep. Castor (D-FL) for introducing the House COPPA 2.0 companion bill. The bill enjoys strong bipartisan support in the U.S. Senate. We urge the House to promptly markup HR 7890 and pass it into law. Any delay in bringing HR 7890 to a vote would expose children, adolescents, and their families to greater harm.Learn more about the Children and Teens’ Online Privacy Protection Act here: Background:The United States is currently facing a commercial surveillance crisis. Digital giants invade our private lives, spy on our families, deploy manipulative and unfair data-driven marketing practices, and exploit our most personal information for profit. These reckless practices are leading to unacceptable invasions of privacy, discrimination, and public health harms.In particular, the United States faces a youth mental health crisis fueled, in part, by Big Tech. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, children’s mental health has reached a national emergency status. The Center for Disease Control found that in 2021, one in three high school girls contemplated suicide, one in ten high school girls attempted suicide, and among LGBTQ+ youth, more than one in five attempted suicide. As the Surgeon General concluded in a report last year, “there are ample indicators that social media can also have a profound risk of harm to the mental health and well-being of children and adolescents.”Platforms’ data practices and their prioritization of profit over the well-being of America’s youth significantly contribute to the crisis. The lack of privacy protections for children and teens has led to a decline in young people’s well-being. Platforms rely on vast amounts of data to create detailed profiles of young individuals to target them with tailored ads. To achieve this, addictive design features are employed, keeping young users online for longer periods of time and exacerbating the youth mental health crisis. The formula is simple: more addiction equals more data and more targeted ads which translates into greater profits for Big Tech. In fact, according to a recent Harvard study, in 2022, the major Big Tech platforms earned nearly $11 billion in ad revenue from U.S. users under age 17.The Children and Teens’ Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA 2.0) modernizes and strengthens the only online privacy law for children, the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA). COPPA was passed over 25 years ago and is crucially in need of an update, including the extension of safeguards to teens. Passed by the Senate out of Committee, Reps. Tim Walberg (R-MI) and Kathy Castor (D-FL) introduced COPPA 2.0 in the House in April. It’s time now for the House to act. The Children and Teens’ Online Privacy Protection Act would:- Build on COPPA and extend privacy safeguards to users who are 13 to 16 years of age;- Require strong data minimization safeguards prohibiting the excessive collection, use, and sharing of children’s and teens’ data; COPPA 2.0 would:Prohibit the collection, use or disclosure or maintenance of personal information for purposes of targeted advertising;Prohibit the collection of personal information except when the collection is consistent with the context and necessary to fulfill a transaction or service or provide a product or service requested;Prohibit the retention of personal information for longer than is reasonably necessary to fulfill a transaction or provide a service;Prohibit conditioning a child’s or teen’s participation on the child’s or teen’s disclosing more personal information than is reasonably necessary.Except for certain internal permissible operations purposes of the operator, all other data collection or disclosures require parental or teen consent.- Ban targeted advertising to children and teens;- Provide for parental or teen controls;It would provide for the right to correct or delete personal information collected from a child or teen or content or information submitted by a child or teen to a website – when technologically feasible.- Revise COPPA’s “actual knowledge” standard to close the loophole that allows covered platforms to ignore kids and teens on their site. But what about….?…Notice and Consent, doesn’t COPPA 2.0 rely on the so-called “notice and consent” approach and isn’t the consensus that this is an ineffective way to protect privacy online?No, COPPA 2.0 does not rely on “notice and consent”. It would provide a comprehensive approach to safeguarding children’s and teen’s privacy via data minimization. It appropriately restricts companies’ ability to collect, use, and share personal information of children and teens by default. The consent mechanism is just one additional safeguard. 1. By default COPPA 2.0 would prohibitthe collection, use or disclosure or maintenance of personal information for purposes of targeted advertising to children and teens - this is a flat out ban, consent is not required.the collection of personal information except when the collection is consistent with the context of the relationship and necessary to fulfill a transaction or service or provide a product or service requested of the relationship of the child/teen with the operator.the retention of personal information for longer than is reasonably necessary to fulfill a transaction or provide a service. 2. By extending COPPA protections to teens, COPPA 2.0 would further limit data collection from children and teens as COPPA 2.0 would prohibitconditioning a child’s or teen’s participation in a game, the offering of a prize, or another activity on the child’s or teen’s disclosing more personal information than is reasonably necessary to participate in such activity. 3. Any other personal information that companies would want to collect, use, or disclose requires parental consent or the consent of a teen, except for certain internal permissible operations purposes of the operator. COPPA 2.0's data minimization provisions prevent the collection, use, disclosure, and retention of excessive data from the start. By not collecting or retaining unnecessary data, harmful, manipulative, and exploitative business practices will be prevented. The consent provision is important but plays a relatively small role in the privacy safeguards of COPPA 2.0. But what about….?…targeted advertising, don’t we need a clear ban of targeted advertising to children and teens?Yes, and COPPA 2.0 bans targeted advertising while allowing for contextual advertising.Under COPPA 2.0 it is unlawful for an operator "to collect, use, disclose to third parties, or maintain personal information of a child or teen for purposes of individual-specific advertising to children or teens (or to allow another person to collect, use, disclose, or maintain such information for such purpose).” But what about….?…the transfer of personal information to third parties?Yes, COPPA 2.0 requires verifiable consent by a parent or teen for the disclosure or transfer of personal information to a third party, except for certain internal permissible operations purposes of the operator. Verifiable consent must be obtained before collection, use, and disclosure of personal information via direct notice of the personal information collection, use, and disclosure practices of the operator. Any material changes from the original purposes also require verifiable consent.(Note that the existing COPPA rule requires that an operator gives a parent the option to consent to the collection and use of the child's personal information without consenting to the disclosure of his or her personal information to third parties under 312.5(a)(2). The FTC recently proposed to bolster this provision under the COPPA rule update.) -

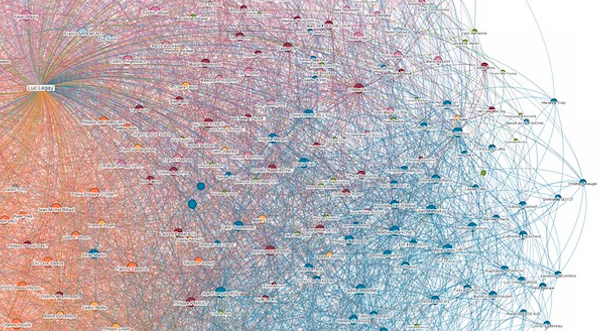

The insatiable quest to acquire more data has long been a force behind corporate mergers in the US—including the proposed combination of supermarket giants Albertsons and Kroger. Both grocery chains have amassed a powerful set of internal “Big Data” digital marketing assets, accompanied by alliances with data brokers, “identity” management firms, advertisers, streaming video networks, and social media platforms. Albertsons and Kroger are leaders in one of the fastest-growing sectors in the online surveillance economy—called “retail media.” Expected to generate $85 billion in ad spending in the US by 2026, and with the success of Amazon as a model, there is a new digital “gold rush” by retailers to cash in on all the loyalty programs, sales information, and other growing ways to target their customers.Albertsons, Kroger, and other retailers including Walmart, CVS, Dollar General and Target find themselves in an enviable position in what’s being called the “post-cookie” era. As digital marketing abandons traditional user-tracking technologies, especially third-party cookies, in order to address privacy regulations, leading advertisers and platforms are lining up to access consumer information they believe comes with less regulatory risk. Supermarkets, drug stores, retailers and video streaming networks have massive amounts of so-called “first-party” authenticated data on consumers, which they claim comes with consent to use for online marketing. That’s why retail media networks operated by Kroger and others, as well as data harvested from streaming companies, are among the hottest commodities in today’s commercial surveillance economy. It’s not surprising that Albertsons and Kroger now have digital marketing partnerships with companies like Disney, Comcast/NBCUniversal, Google and Meta—to name just a few.The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is currently reviewing this deal, which is a test case of how well antitrust regulators address the dominant role that data and the affordances of digital marketing play in the marketplace. The “Big Data” digital marketing era has upended many traditional marketplace structures; consolidation is accompanied by a string of deals that further coalesces power to incumbents and their allies. What’s called “collaboration”—in which multiple parties work together to extend individual and collective data capabilities—is now a key feature operating across the broader online economy, and is central to the Kroger/Albertsons transaction. Antitrust law has thus far failed to address one of the glaring threats arising from so many mergers today—their impact on privacy, consumer protection, and diversity of media ownership. Consider all the transactions that the FTC and Department of Justice have allowed in recent years, such as the scores of Google and Facebook acquisitions, and what deleterious impact they had on competition, data protection, and other societal outcomes.Under Chair Lina Khan, the FTC has awakened from what I have called its long “digital slumber,” moving to the forefront in challenging proposed mergers and working to develop more effective privacy safeguards. My organization told the commission that addressing the current role data-driven marketing plays in the Albertsons and Kroger merger, and how consolidating the two digital operations is really central to the two companies’ goals for the deal, must be part of its antitrust case.Kroger has been at the forefront of understanding how the sales and marketing of groceries and other consumer products have to operate simultaneously in-store and online. It acquired a leading “retail, data science, insights and media” company in 2015—which it named 84.51° after its geo coordinates in Cincinnati. Today, 84.51° touts its capabilities to leverage “data from over 62 million households” in influencing consumer buying behavior “both in-store and online,” using “first party retail data from nearly 1 of 2 US households and more than two billion transactions.” Kroger’s retail media division—called “Precision Marketing”—draws on the prowess of 84.51° to sell a range of sophisticated data targeting opportunities for advertisers, including leading brands that stock its in-store and online shelves. For example, ads can be delivered to customers when they search for a product on the Kroger website or its app; when they view digital discount coupons; and when customers are visiting non-Kroger-owned sites.These initiatives have created a number of opportunities for Kroger to make money from data. Last year, Precision Marketing opened its “Private Marketplace” service that enables advertisers to access Kroger customers via targeting lists of what are known as “pre-optimized audiences” (groups of consumers who have been analyzed and identified as potential customers for various products). Like other retailers, Kroger has a data and ad deal with video streaming companies, including Disney and Roku. Its alliance with Disney enables it to take advantage of that entertainment company’s major data-marketing assets, including AI tools and the ability to target consumers using its “250 million user IDs.”Likewise, the Albertsons “Media Collective” division promises advertisers that its retail media “platform” connects them to “over 100 million consumers.” It offers similar marketing opportunities for grocery brands as Kroger, including targeting on its website, app and also when its customers are off-site. Albertsons has partnerships across the commercial surveillance advertising spectrum, including with Google, the Trade Desk, Pinterest, Criteo and Meta/Facebook. It also has a video streaming data alliance involving global advertising agency giant Omnicom that expands its reach with viewers of Comcast’s NBCUniversal division, as well as with Paramount and Warner Bros./Discovery.Both Kroger and Albertsons partner with many of the same powerful identity-data companies, including data-marketing and cross-platform leaders LiveRamp and the Trade Desk. Through these relationships, the two grocery chains are connected to a vast network of databrokers that provide ready access to customer health, financial, and geolocation information, for example. The two grocery chains also work with the same “retail data cloud” company that further extends their marketing impact. Further compounding the negative competitive and privacy threats from this deal is its role in providing ongoing “closed-loop” consumer tracking to better perfect the ways retailers and advertisers measure the effectiveness of their marketing. They know precisely what you bought, browsed and viewed—in store and at home.Antitrust NGOs, trade unions and state attorneys-general have sounded the alarm about the pending Albertsons/Kroger deal, including its impact on prices, worker rights and consumer access to services. As the FTC nears a decision point on this merger, it should make clear that such transactions, which undermine competition, privacy, and expand the country’s commercial surveillance apparatus, should not be permitted.This article was originally published by Tech Policy Press.

-

Blog

Is So-called Contextual Advertising the Cure to Surveillance-based “Behavioral” Advertising?

Contextual advertising might soon rival or even surpass behavioral advertising’s harms unless policy makers intervene

Contextual advertising is said to be privacy-safe because it eliminates the need for cookies, third-party trackers, and the processing of other personal data. Marketers and policy makers are placing much stock in the future of contextual advertising, viewing it as the solution to the privacy-invasive targeted advertising that heavily relies on personal data.However, the current state of contextual advertising does not look anything like our plain understanding of it in contrast to today's dominant mode of behavioral advertising: placing ads next to preferred content, based on keyword inclusion or exclusion. Instead, industry practices are moving towards incorporating advanced AI analysis of content and its classification, user-level data, and insights into content preferences of online visitors, all while still referring to “contextual advertising.” It is crucial for policymakers to carefully examine this rapidly evolving space and establish a clear definition of what “contextual advertising” should entail. This will prevent the emergence of toxic practices and outcomes, similar to what we have witnessed with surveillance-based behavioral marketing, from becoming the new normal.Let’s recall the reasons for the strong opposition to surveillance-based marketing practices so we can avoid those harms regarding contextual advertising. Simply put, the two main reasons are privacy harms and harms from manipulation. Behavioral advertising is deeply invasive when it comes to privacy, as it involves tracking users online and creating individual profiles based on their behavior over time and across different platforms and across channels. These practices go beyond individual privacy violations and also harm groups of people, perpetuating or even exacerbating historical discrimination and social inequities.The second main reason why many oppose surveillance-based marketing practices is the manipulative nature of commercial messaging that aims to exploit users’ vulnerabilities. This becomes particularly concerning when vulnerable populations, like children, are targeted, as they may not have the ability to resist sophisticated influences on their decision-making. More generally, the behavioral advertising business heavily incentivizes companies to optimize their practices for monetizing attention and selling audiences to advertisers, leading to many associated harms.New and evolving practices in contextual advertising should raise questions for policy makers. They should consider whether the harms we sought to avoid with behavioral marketing may resurface in these new advertising practices as well.Today’s contextual advertising methods are taking advantage of the latest analytical technologies to interpret online content so that contextual ads will likely soon be able to manipulate us just as behavioral ads can. Artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, natural language processing models for tone and sentiment analysis, computer vision, audio analysis, and more are being used to consider a multitude of factors and in this way “dramatically improve the effectiveness of contextual targeting.” Gumgum’s Verity, for example, “scans text, image, audio and video to derive human-like understandings.” Attention measures – the new performance metric that advertisers crave – indicate that contextual ads are more effective than non-contextual ads. Moments.AI, a “real-time contextual targeting solution” by the Verve Group, for example, allows brands to move away from clicks and to “optimize towards consumer attention instead,” for “privacy-first” advertising solutions.Rather than analyzing one single URL or one article at a time, marketers can analyze a vast range of URLs and can “understand content clusters and topics that audiences are engaging with at that moment” and so use contextual targeting at scale. The effectiveness and sophistication of contextual advertising allows marketers to use it not just for enhancing brand awareness, but also for targeting prospects. In fact, the field of “neuroprogammatic” advertising “goes beyond topical content matching to target the subconscious feelings that lead consumers to make purchasing decisions,” according to one industry observer. Marketers can take advantage of how consumers “are feeling and thinking, and what actions they may or may not be in the mood to take, and therefore how likely are to respond to an ad. Neuroprogrammatic targeting uses AI to cater to precisely what makes us human.”These sophisticated contextual targeting practices may have negative effects similar to those of behavioral advertising, however. For instance, contextual ads on weight loss programs can be placed alongside content related to dieting and eating disorders due to its semantic, emotional, and visual content. This may have disastrous consequences similar to targeted behavioral ads aimed at teenagers with eating disorders. Therefore, it is important to question how different these practices are from individual user tracking and ad targeting. If content can be analyzed and profiled along very finely tuned classification schemes, advertisers don’t need to track users across the web. They simply need to track the content that will deliver the relevant audience and engage individuals based on their interests and feelings.Apart from the manipulative nature of contextual advertising, the use of personal data and associated privacy violations are also concerning. Many contextual ad tech companies claim to engage in contextual targeting “without any user data.” But, in fact, so-called contextual ad tech companies often rely on session data such as browser and page-level data, device and app-level data, IP address, and “whatever other info they can get their hands on to model the potential user,” framing it as “contextual 2.0.” Until recently, this practice might have been more accurately referred to as device fingerprinting. The claim is that session data is not about tracking, but only about the active session and usage at one point in time. No doubt, however, the line between contextual and behavioral advertising becomes blurry when such data is involved.Location-based targeting is another aspect of contextual advertising that raises privacy concerns. Should location-based targeting be considered contextual? Uber’s “Journey Ads” lets advertisers target users based on their destination. A trip to a restaurant might trigger alcohol ads; a trip to the movie theater might result in ads for sugary beverages. According to AdExchanger, Uber claims that it is not “doing any individual user-based targeting” and suggests that it is a form of contextual advertising.Peer 39 also includes location data in its ad-targeting capabilities and still refers to these practices as contextual advertising. The use of location data can reveal some of the most sensitive information about a person, including where she works, sleeps, socializes, worships, and seeks medical treatment. When combined with session data, the information obtained from sentiment, image, video, and location analysis can be used to create sophisticated inferences about individuals, and ads placed in this context can easily clash with consumer expectations of privacy.Furthermore, placing contextual ads next to user-generated content or within chat groups changes the parameters of contextual targeting. Instead of targeting the content itself, the ad becomes easily associated with an individual user. Reddit’s “contextual keyword targeting” allows advertisers to target by community and interests, discussing LGBTQ+ sensitive topics, for example. This is similar to the personalized nature of targeted behavioral advertising, and can thus raise privacy concerns.Cohort targeting, also referred to as “affinity targeting” or “content affinity targeting,” further blurs the line between behavioral and contextual advertising by combining content analytics with audience insights. “This bridges the gap between Custom Cohorts and your contextual signals, by taking learning from consented users to targeted content where a given Customer Cohort shows more engagement than the site average,” claims Permutive.Oracle uses various cohorts with demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and income, for example, as well as “lifestyle” and “retail” interests, to understand what content individuals are more likely to consume. While reputedly “designed for privacy from the ground up,” this approach allows Oracle to analyze what an audience cohort views and to “build a profile of the content types they’re most likely to engage with,” allowing advertisers to find their “target customers wherever they are online.” Playground XYZ enhances contextual data with eye-tracking data from opt-in panels, which measures attention and helps to optimize which content is most “eye-catching,” “without the need for cookies or other identifiers.”Although these practices may seem privacy neutral (relying on small samples of online users or “consented users”), they still allow advertisers to target and manipulate their desired audience. Message targeting based on content preferences of fine-tuned demographic characteristics (household income less than $20K or over $500K, for example) can lead to discriminatory practices and disparate impact that can deepen social inequities, just like the personalized targeting of online users.Hyper-contextual content analysis with a focus on measuring sentiment and attention, the use of session information, placing ads next to user-generated content as well as within interest group chats, and employing audience panels to profile content are emerging practices in contextual advertising that require critical examination. The touted privacy-first promise of contextual advertising is deceptive. It seems that contextual advertising is more manipulative, invasive of privacy, and likely to contribute to discrimination and perpetuate inequities among consumers than we all initially thought.What’s more, the convergence of highly sensitive content analytics with content profiling based on demographic characteristics (and potentially more), could result in even more potent digital marketing practices than those currently being deployed. By merging contextual data with behavioral data, marketers might gain a more comprehensive understanding of their target audience and develop more effective messaging. Additionally, we can only speculate about how modifications to the incentive structure for content delivery of audiences to advertisers might impact content quality.In the absence of policy intervention, these developments may lead to a surveillance system that is even more formidable than the one we currently have. Contextual advertising will not serve as a solution to surveillance-based “behavioral” marketing and its manipulative and privacy invasive nature, let alone the numerous other negative consequences associated with it, including the addictive nature of social media, the promotion of disinformation, and threats to public health.It is vital to formulate a comprehensive and up-to-date definition of contextual advertising that takes into consideration the adverse effects of surveillance advertising and strives to mitigate them. Industry self-regulation cannot be relied on, and legislative proposals do not adequately address the complexities of contextual advertising. The FTC’s 2009 definition of contextual advertising is also outdated in light of the advancements and practices described here. Regulatory bodies like the FTC must assess contemporary practices and provide guidelines to safeguard consumer privacy and ensure fair marketing practices. The FTC’s Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act rule update and its Commercial Surveillance and Data Security Rule provide opportunity to get it right.Failure to intervene may ultimately result in the emergence of a surveillance system disguised as consumer-friendly marketing. This article was originally published by Tech Policy Press. -

Blog

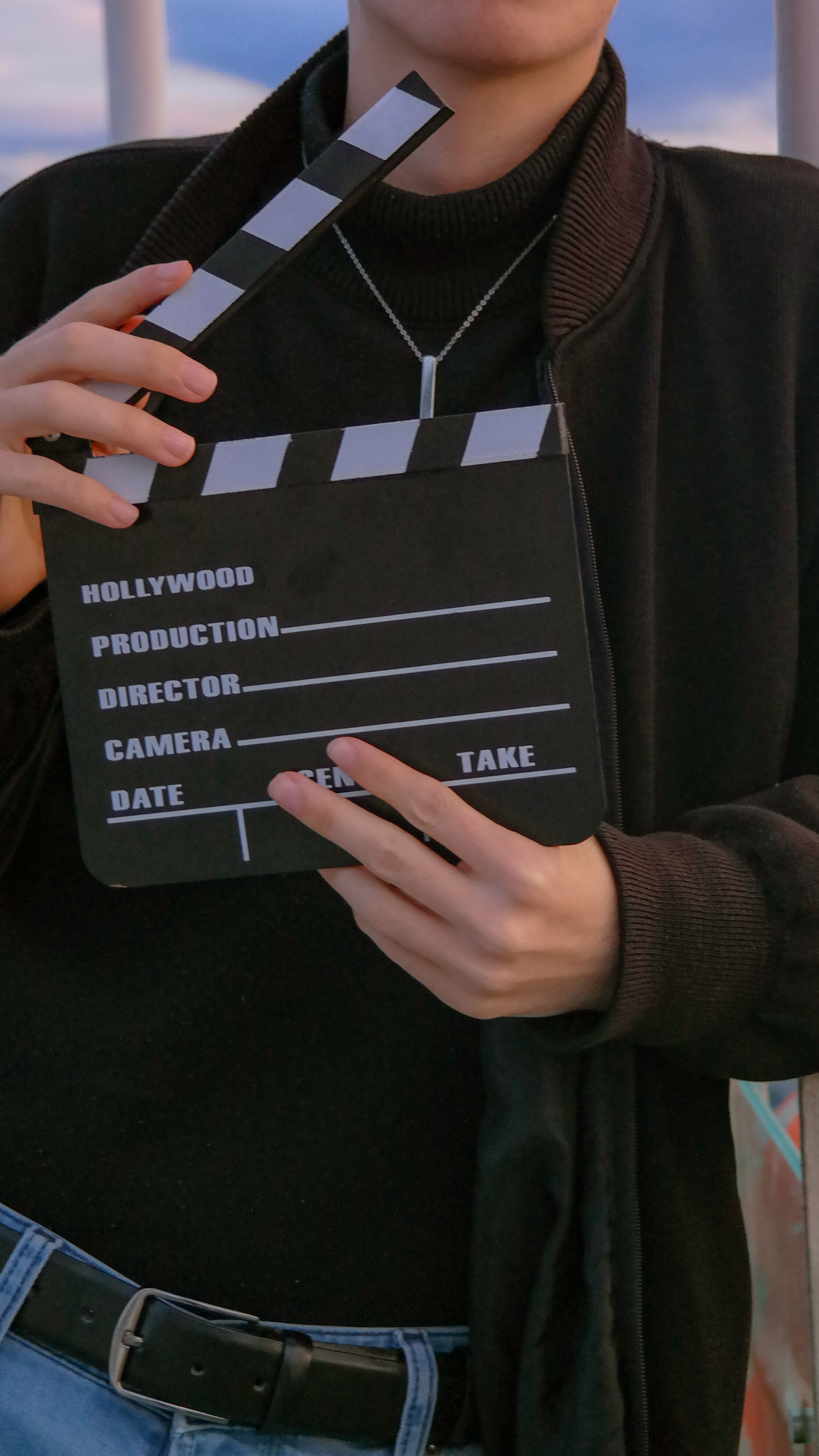

Profits, Privacy and the Hollywood Strike

Addressing commercial surveillance in streaming video is key to any deal for workers and viewers says Jeff Chester, the executive director of the Center for Digital Democracy.

Leading studios, networks and production companies in Hollywood—such as Disney, Paramount, Comcast/NBCU, Warner Bros. Discovery and Amazon—know where their dollars will come from in the future. As streaming video becomes the dominant form of TV in the U.S., the biggest players in the entertainment industry are harvesting the cornucopia of data increasingly gathered from viewers. While some studio chiefs publicly chafe over the demands from striking actors and writers as being unrealistic, they know that their heavy investments in “adtech” will drive greater profitability. Streaming video data not only generates higher advertising and commerce revenues, but also serves as a valuable commodity for the precise online tracking and targeting of consumers.Streaming video is now a key part in what the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) calls the “commercial surveillance” marketplace. Data about our viewing behaviors, including any interactions with the content, is being gathered by connected and “smart” TVs, streaming devices such as Roku, in-house studio and network data mining operations, and by numerous targeting and measurement entities that now serve the industry. For example, Comcast’s NBCUniversal “One Platform” uses what it calls “NBCU ID”—a “first-party identifier [that] provides a persistent indicator of who a consumer is to us over time and across audiences.” Last year it rolled out “200 million unique person-level NBCU IDs mapped to 80 million households.” Disney’s Select advertising system uses a “proprietary Audience Graph” incorporating “100,000 attributes” to help “1800 turnkey” targeting segments. There are 235 million device IDs available to reach, says Disney, 110 million households. It also operates a “Disney Real-time Ad Exchange (DRAX), a data clean room and what it calls “Yoda”—a “yield optimized delivery allocation” empowering its ad server.Warner Bros. Discovery recently launched “WBD Stream,” providing marketers with “seamless access… to popular and premium content.” It also announced partnerships with several data and research companies designed to help “marketers to push consumers further down the path to purchase.” One such alliance involves “605,” which helps WBD track how effective its ads are in delivering actual sales from local retailers, including the use of set-top box data from Comcast as well as geolocation tracking information. Amazon has long supported its video streaming advertising sales, including with its “Freevee” network, through its portfolio of cutting-edge data tools. Among the ad categories targeted by Amazon’s streaming service are financial services, candy and beauty products. One advantage it touts is that streaming marketers can get help from “Amazon’s Ads data science team,” including an analysis of “signals in [the] Amazon Marketing Cloud.”Other major players in video streaming have also supercharged their data technologies, including Roku, Paramount, and Samsung, in order to target what are called “advanced audiences.” That’s the capability to have so much information available that a programmer can pinpoint a target for personalized marketing across a vast universe of media content. While subscription is a critical part of video revenues, programmers want to draw from multiple revenue streams, especially advertising. To help advance the ability of the TV business to have access to more thorough datasets, leading TV, advertising and measurement companies have formed the “U.S. Joint Industry Committee” (JIC). Warner Bros. Discovery, Fox, NBCU, TelevisaUnivision, Paramount, and AMC are among the programmers involved with JIC. They are joined by a powerhouse composed of the largest ad agencies (data holders as well), including Omnicom, WPP and Publicis. One outcome of this alliance will be a set of standards to measure the impact of video and other ads on consumers, including through the use of “Big Data” and cross-platform measurement.Of course, today’s video and filmed entertainment business includes more than ad-supported services. There’s subscription revenue for streaming–said to pass $50 billion for the U.S. this year– as well as theatrical release. But it’s very evident that the U.S. (as well as the global) entertainment business is in a major transition, where the requirement to identify, track and target an individual (or groups of people) online and as much offline as possible is essential. For example, Netflix is said to be exploring ways it can advance its own solution to personalized ad targeting, drawing its brief deal with Microsoft Advertising to a close. Leading retailers, including Walmart (NBCU) and Kroger (Disney), are also part of today’s streaming video advertising landscape. Making the connections to what we view on the screen and then buy at a store is a key selling point for today’s commercial surveillance-oriented streaming video apparatus. A growing part of the revenue from streaming will be commissions from the sale of a product after someone sees an ad and buys that product, including on the screen during a program. For example, as part of its plans to expand retail sales within its programming, NBCU’s “Checkout” service “identifies objects in video and makes them interactive and shoppable.”Another key issue for the Hollywood unions is the role of AI. With that technology already a core part of the advertising industry’s arsenal, its use will likely be integrated into video programming—something that should be addressed by the SAG-AFTRA and WGA negotiations.The unions deserve to capture a piece of the data-driven “pie” that will further drive industry profits. But there’s more at stake than a fair contract and protections for workers. Rather than unleashing the creativity of content providers who are part of a environment promoting diversity, equity and the public interest, the new system will be highly commercialized, data driven, and controlled by a handful of dominant entities. Consider the growing popularity of what are called “FAST” channels—which stands for “free ad supported streaming television.” Dozens of these channels, owned by Comcast/NBCU, Paramount, Fox, and Amazon, are now available, and filled with relatively low-cost content that can reap the profits from data and ads.The same powerful forces that helped undermine broadcasting, cable TV, and the democratic potential of what once was called the “information superhighway”—the Internet—are now at work shaping the emerging online video landscape. Advertising and marketing, which are already the influence behind the structure and affordances of digital media, are fashioning video streaming to be another—and critically important—component fostering surveillance marketing.The FTC’s forthcoming proposed rulemaking on commercial surveillance must address the role of streaming video. And the FCC should open up its own proceeding on streaming, one designed to bring structural changes to the industry in terms of ownership of content and distribution. There’s also a role for antitrust regulators to examine the data partnerships emerging from the growing collaboration by networks and studios to pool data resources. The fight for a fairer deal for writers and actors deserves the backing of regulators and the public. But a successful outcome for the strike should be just “Act One” of a comprehensive digital media reform effort. While the transformation of the U.S. TV system is significantly underway, it’s not too late to try to program “democracy” into its foundation. Jeff Chester is the executive director of the Center for Digital Democracy, a DC-based NGO that works to ensure that digital technologies serve and strengthen democratic values and institutions. Its work on streaming video is supported, in part, by the Rose Foundation for Communities and the Environment.This op-ed was initially published by the Tech Policy Press. -

Meta’s Virtual Reality-based Marketing Apparatus Poses Risks to Teens and OthersWhether it’s called Facebook or Meta, or known by its Instagram, WhatsApp, Messenger or Reels services, the company has always seen children and teens as a key target. The recent announcement opening(link is external) up the Horizon Worlds metaverse(link is external) to teens, despite calls to first ensure it will be a safe and healthy experience, is lifted out of Facebook’s well-worn political playbook—make whatever promises necessary to temporarily quell any political opposition to its monetization plans. Meta’s priorities are intractably linked to its quarterly shareholder revenue reports. Selling our “real” and “virtual” selves to marketers is their only real source of revenue, a higher priority than any self-regulatory scheme Meta offers(link is external) claiming to protect children and teens.Meta’s focus on creating more immersive, AI/VR, metaverse-connected experiences for advertisers should serve as a “wake-up” call for regulators. Meta has unleashed a digital environment designed to trigger the “engagement(link is external)” of young people with marketing, data collection and commercially driven manipulation. Action is required to ensure that young people are treated fairly, and not exposed to data surveillance, threats to their health and other harms.Here are a few recent developments that should be part of any regulatory review of Meta and young people:Expansion of “immersive(link is external)” video and advertising-embedded applications: Meta tells marketers it provides “seamless video experiences that are immersive and fueled by discovery,” including the “exciting(link is external) opportunity for advertisers” with its short-video “Reels” system. Through virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR(link is external)) technologies, we are exposed to advertising content designed to have a greater impact by influencing our subconscious and emotional processes. With AR ads, Meta tells(link is external) marketers, they can “create immersive experiences, encourage people to virtually try out your products and inspire people to interact with your brand,” including encouraging “people who interact with your ad… [to]take photos or videos to share their experience on Facebook Feed, on Facebook and Instagram Stories or in a message on Instagram.” Meta has also been researching(link is external) the use of AR(link is external) and VR(link is external) that will ensure that its ad and marketing messaging becomes even more compelling.Expanded integration of ads throughout Meta applications: Meta allows advertisers to “turn organic image and video posts into ads in Ads Manager on Facebook Reels,” including adding a “call-to-action” feature. It permits marketers to “boost their Reels within the Instagram app to turn them into ads….” It enables marketers “to add a “Send Message” button to their Facebook Reels ads [that] give people an option to start a conversation in WhatsApp(link is external) right from the ad.” This follows last year’s Meta “Boosted Reels” product(link is external) release, allowing Instagram Reels to be turned into ads as well.“Ads Manager” “optimization(link is external) goals” that are inappropriate when used for targeting young people: These include “impressions, reach, daily unique reach, link clicks and offsite conversions.” “Ad placements” to target teens are available for the “Facebook Marketplace, Facebook Feed, … Facebook Stories, Facebook-instream video (mobile), Instagram Feed, Instagram Explore, Instagram Stories, Facebook Reels and Instagram Reels.”The use of metrics for delivering and measuring the impact of augmented reality ads: As Meta explains, it uses:(link is external)Instant Experience View Time: The average total time in seconds that people spent viewing an Instant Experience. An Instant Experience can include videos, images, products from a catalog, an augmented reality effect and more. For an augmented reality ad, this metric counts the average time people spent viewing your augmented reality effect after they tapped your ad.Instant Experience Clicks to Open: The number of clicks on your ad that open an Instant Experience. For an augmented reality ad, this metric counts the number of times people tapped your ad to open your augmented reality effect.Instant Experience Outbound Clicks: The number of clicks on links in an Instant Experience that take people off Meta technologies. For an augmented reality ad, this metric counts the number of times people tapped the call to action button in your augmented reality effect.Effect Share: The number of times someone shared an image or video that used an augmented reality effect from your ad. Shares can be to Facebook or Instagram Stories, to Facebook Feed or as a message on Instagram.These ad effects can be designed and tested(link is external) through Meta’s “Spark Hub” and ad manager. Such VR and other measurement systems require regulators to analyze their role and impact on youth.Expanded use of machine learning/AI to promote shopping via Advantage(link is external)+: Last year, Meta rolled out “Advantage+ shopping campaigns, Meta’s machine-learning capabilities [that] save advertisers(link is external) time and effort while creating and managing campaigns. For example, advertisers can set up a single Advantage+ shopping campaign, and the machine learning-powered automation automatically combines prospecting and retargeting audiences, selects numerous ad creative and messaging variations, and then optimizes for the best-performing ads.” While Meta says that Advantage+ isn’t used to target teens, it deploys(link is external) it for “Gen Z” audiences. How Meta uses machine learning/AI to target families should also be on the regulatory agenda.Immersive advertising will shape the near-term evolution of marketing, where brands will be “world agnostic and transcend the limitations of the current physical and digital space.” The Advertising Research Foundation (ARF) predicts(link is external) that “in the next decade, AR and VR hardware and software will reach ubiquitous status.” One estimate is that by 2030, the metaverse will “generate(link is external) up to $5 trillion in value.”In the meantime, Meta’s playbook in response to calls from regulators and advocates is to promise some safeguards, often focused on encouraging the use of what it calls “safety(link is external) tools.” But these tools(link is external) do not ensure that teens aren’t reached and influenced by AI- and VR-driven marketing technologies and applications. Meta also knows that today, ad-targeting is less important than so-called “discovery(link is external),” where its purposeful melding of its video content, AR effects, social interactions and influencer marketing will snare young people into its marketing “conversion”(link is external) net.Last week, Mark Zuckerberg told(link is external) investors his vision of bringing “AI agents to billions of people,” as well as into his “metaverse” that will be populated by “avatars, objects, worlds, and codes to tie” online and offline together. There will be, as previously reported, an AI-driven “discovery(link is external) engine” that will “increase the amount of suggested content to users.”These developments reflect just a few of the AI- and VR-marketing-driven changes to the Meta system. They illustrate why responsible regulators and advocates must be in the forefront of holding this company accountable, especially with regard to its youth-targeting apparatus.Please also read(link is external) Fairplay for Kids’ account of Meta’s long history of failing to protect children online. metateensaivr0523fin.pdfJeff Chester

-

FTC Commercial Surveillance Filing from CDD focuses on how pharma & other health marketers target consumers, patients, prescribers “Acute Myeloid Lymphoma,” “ADHD,” “Brain Cancer,” “High Cholesterol,” “Lung Cancer,” “Overweight,” “Pregnancy,” “Rheumatoid Arthritis,” “Stroke,” and “Thyroid Cancer.” These are just a handful of the digitally targetable medical condition “audience segments” available to surveillance advertisers While health and medical condition marketers—including pharmaceutical companies and drug store chains—may claim that such commercial data-driven marketing is “privacy-compliant,” in truth it reveals how vulnerable U.S. consumers are to having some of their most personal and sensitive data gathered, analyzed, and used for targeted digital advertising. It also represents how the latest tactics leveraging data to track and target the public—including “identity graphs,” artificial intelligence, surveilling-connected or smart TV devices, and a focus on so-called permission-based “first-party data”—are now broadly deployed by advertisers—including pharma and medical marketers. Behind the use of these serious medical condition “segments” is a far-reaching commercial surveillance complex including giant platforms, retailers, “Adtech” firms, data brokers, marketing and “experience” clouds, device manufacturers (e.g., streaming), neuromarketing and consumer research testing entities, “identity” curation specialists and advertisers...We submit as representative of today’s commercial surveillance complex the treatment of medical condition and health data. It incorporates many of the features that can answer the questions the commission seeks. There is widespread data gathering on individuals and communities, across their devices and applications; techniques to solicit information are intrusive, non-transparent, and out of meaningful scope for consumer control; these methods come at a cost to a person’s privacy and pocketbook, and potentially has significant consequences to their welfare. There are also societal impacts here, for the country’s public health infrastructure as well as with the expenditures the government must make to cover the costs for prescription drugs and other medical services...Health and pharma marketers have adopted the latest data-driven surveillance-marketing tactics—including targeting on all of a consumer’s devices (which today also includes streaming video delivered by Smart TVs); the integration of actual consumer purchase data for more robust targeting profiles; leveraging programmatic ad platforms; working with a myriad of data marketing partners; using machine learning to generate insights for granular consumer targeting; conducting robust measurement to help refine subsequent re-targeting; and taking advantage of new ways to identify and reach individuals—such as “Identity Graphs”— across devices. [complete filing for the FTC's Commercial Surveillance rulemaking attached]cddsurveillancehealthftc112122.pdfJeff Chester

-

Commercial Surveillance expands via the "Big" Screen in the Home Televisions now view and analyze us—the programs we watch, what shows we click on to consider or save, and the content reflected on the “glass” of our screens. On “smart” or connected TVs, streaming TV applications have been engineered to fully deliver the forces of commercial surveillance. Operating stealthily inside digital television sets and streaming video devices is an array of sophisticated “adtech” software. These technologies enable programmers, advertisers and even TV set manufacturers to build profiles used to generate data-driven, tailored ads to specific individuals or households. These developments raise important questions for those concerned about the transparency and regulation of political advertising in the United States.Also known as “OTT” (“over-the-top” since the video signal is delivered without relying on traditional set-top cable TV boxes), the streaming TV industry incorporates the same online advertising techniques employed by other digital marketers. This includes harvesting a cornucopia of information on viewers through alliances with leading data-brokers. More than 80 percent of Americans now use some form of streaming or Smart TV-connected video service. Given such penetration, it is no surprise that streaming TV advertising is playing an important role in the upcoming midterm elections. And, streaming TV will be an especially critical channel for campaigns to vie for voters in 2024. Unlike political advertising on broadcast television or much of cable TV, which is generally transmitted broadly to a defined geographic market area, “addressable” streaming video ads appear in programs advertisers know you actually watch (using technologies such as dynamic ad insertion). Messaging for these ads can also be fine-tuned as a campaign progresses, to make the message more relevant to the intended viewer. For example, if you watch a political ad and then sign up to receive campaign literature, the next TV commercial from a candidate or PAC can be crafted to reflect that action. Or, if your data profile says you are concerned about the costs of healthcare, you may see a different pitch than your nextdoor neighbor who has other interests. Given the abundance of data available on households, including demographic details such as race and ethnicity, there will also be finely tuned pitches aimed at distinct subcultures produced in multiple languages.An estimated $1.4 billion dollars will be spent on streaming political ads for the midterms (part of an overall $9 billion in ad expenditures). With more people “cutting the cord” by signing up for cheaper, ad-supported streaming services, advances in TV technologies to enable personalized data-driven ad targeting, and the integration of streaming TV as a key component of the overall online marketing apparatus, it is evident that the TV business has changed. Even what’s considered traditional broadcasting has been transformed by digital ad technologies. That’s why it’s time to enact policy safeguards to ensure integrity, fairness, transparency and privacy for political advertising on streaming TV. Today, streaming TV political ads already combine information from voter records with online and offline consumer profile data in order to generate highly targeted messages. By harvesting information related to a person’s race and ethnicity, finances, health concerns, behavior, geolocation, and overall digital media use, marketers can deliver ads tied to our needs and interests. In light of this unprecedented marketing power and precision, new regulations are needed to protect consumer privacy and civic discourse alike. In addition to ensuring voter privacy, so personal data can’t be as readily used as it is today, the messaging and construction of streaming political ads must also be accountable. Merely requiring the disclosure of who is buying these ads is insufficient. The U.S. should enact a set of rules to ensure that the tens of thousands of one-to-one streaming TV ads don’t promote misleading or false claims, or engage in voter suppression and other forms of manipulation. Journalists and campaign watchdogs must have the ability to review and analyze ads, and political campaigns need to identify how they were constructed—including the information provided by data brokers and how a potential voter’s viewing behaviors were analyzed (such as with increasingly sophisticated machine learning and artificial intelligence algorithms). For example, data companies such as Acxiom, Experian, Ninth Decimal, Catalina and LiveRamp help fuel the digital video advertising surveillance apparatus. Campaign-spending reform advocates should be concerned. To make targeted streaming TV advertising as effective as possible will likely require serious amounts of money—for the data, analytics, marketing and distribution. Increasingly, key gatekeepers control much of the streaming TV landscape, and purchasing rights to target the most “desirable” people could face obstacles. For example, smart TV makers– such as LG, Roku, Vizio and Samsung– have developed their own exclusive streaming advertising marketplaces. Their smart TVs use what’s called ACR—”automated content recognition”—to collect data that enables them to analyze what appears on our screens—“second by second.” An “exclusive partnership to bring premium OTT inventory to political clients” was recently announced by LG and cable giant Altice’s ad division. This partnership will enable political campaigns that qualify to access 30 million households via Smart TVs, as well as the ability to reach millions of other screens in households known to Altice. Connected TVs also provide online marketers with what is increasingly viewed as essential for contemporary digital advertising—access to a person’s actual identity information (called “first-party” data). Streaming TV companies hope to gain permission to use subscriber information in many other ways. This practice illustrates why the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) current initiative designed to regulate commercial surveillance, now in its initial stage, is so important. Many of the critical issues involving streaming political advertising could be addressed through strong rules on privacy and online consumer protection. For example, there is absolutely no reason why any marketer can so easily obtain all the information used to target us, such as our ethnicity, income, purchase history, and education—to name only a few of the variables available for sale. Nor should the FTC allow online marketers to engage in unfair and largely stealth tactics when creating digital ads—including the use of neuroscience to test messages to ensure they respond directly to our subconscious. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which has largely failed to address 21st century video issues, should conduct its own inquiry “in the public interest.” There is also a role here for the states, reflecting their laws on campaign advertising as well as ensuring the privacy of streaming TV viewers.This is precisely the time for policies on streaming video, as the industry becomes much more reliant on advertising and data collection. Dozens of new ad-supported streaming TV networks are emerging—known as FAST channels (Free Ad Supported TV)—which offer a slate of scheduled shows with commercials. Netflix and Disney+, as well as Amazon, have or are soon adopting ad-supported viewing. There are also coordinated industry-wide efforts to perfect ways to more efficiently target and track streaming viewers that involve advertisers, programmers and device companies. Without regulation, the U.S. streaming TV system will be a “rerun” of what we historically experienced with cable TV—dashed expectations of a medium that could be truly diverse—instead of a monopoly—and also offer both programmers and viewers greater opportunities for creative expression and public service. Only those with the economic means will be able to afford to “opt-out” of the advertising and some of the data surveillance on streaming networks. And political campaigns will be allowed to reach individual voters without worry about privacy and the honesty of their messaging. Both the FTC and FCC, and Congress if it can muster the will, have an opportunity to make streaming TV a well-regulated, important channel for democracy. Now is the time for policymakers to tune in.***This essay was originally published by Tech Policy Press.Support for the Center for Digital Democracy’s review of the streaming video market is provided by the Rose Foundation for Communities and the Environment.Jeff Chester

-

Blog

Protecting Children and Teens from Unfair and Deceptive Marketing, including Stealth Advertising